The drive from San Diego to Lassen Volcanic National Park has become so familiar that we navigate the majority of the way without GPS. It’s a good exercise for the memory, helps us feel closer to the road, and is certainly better for our smartphones’ battery life.

This brings to mind a strange paradox. We recently watched a video of a solo hitchhiker in Mauritania—a country of vast deserts, unpaved roads, and a sparse population. Yet, in every car, the driver and passengers were browsing their phones, implying near-constant internet coverage. In contrast, here in the deserts of Southern California, reliable mobile internet is a luxury found mostly in urban areas, even though a smartphone is in every pocket.

Our well-worn path begins on I-15, navigating the sprawl of Los Angeles before escaping onto US-395 North through Hesperia, Kramer Junction, and Johannesburg. Our first traditional stop is Ridgecrest, a necessary pause to stock up on water, food, and especially cold ice cream to combat the 100°F+ heat where shade is a rare commodity.

Back on US-395, the landscape transforms. We pass the starkly beautiful lava flows of the Coso Volcanic Field—a name derived from the Shoshone word kosoowa, meaning “be steamy.” We admire Red Hill, a classic cinder cone formed during the Pleistocene, and drive along the vast bed of the former Owens Lake, known as Patsiata to the Nüümü people. It stands as a monument to a dramatic story: from a vibrant ecosystem to an environmental disaster, and now, to a site of remarkable ecological renewal. Sarcastically, the Paiute name for the entire Owens Valley, that holds the lake and river Wakopee (in Paiute), Payahuunadü, beautifully translates to “the land of flowing water.”

Our second traditional stop is the Eastern Sierra Visitor Center in Lone Pine for a fifteen-minute rest, admiring the breathtaking panorama of the Sierra Nevada. The view is dominated by Mount Whitney, called Tumanguya (“the very old man”) by the Paiute, and the jumbled rock formations of the Alabama Hills. Also visible is Kearsarge Pinnacles, a peak whose name holds a wonderful irony. The nearby Alabama Hills were named by Confederate sympathizers for the warship CSS Alabama, while Kearsarge Pinnacles was named by Union supporters for the USS Kearsarge—the ship that ultimately sank the Alabama in 1864.

Interestingly, while the granite of the rounded Alabama Hills and the steep Sierra backdrop are from the same ancient origin (formed 85-200 million years ago as magma cooled deep underground), the landscapes themselves are vastly different in age. The jagged Sierra Nevada range began its dramatic uplift only about 10 million years ago, accelerating in the last 3 to 5 million. The Alabama Hills, in contrast, have been subjected to a much longer and slower process of weathering and erosion, giving them their ancient, rounded appearance.

An optional but recommended stop is the gas station at the Fort Independence Indian Reservation, known for its reliably cheap prices. This is the home of the Fort Independence Paiute Tribe, guardians of the vital Independence Creek. The reservation is named after Camp Independence, a U.S. Army post established during the Civil War to guard the route to the gold and slver mines in the Eastern Sierra. In 15 years, in 1877, the fort was abandoned, and the reservation was officially established in 1915 on land near the old fort.

Next is Big Pine, a town we strongly associate with the turnoff to the Ancient Bristlecone Pine Forest with the oldest living non-clonal organisms on the Earth, “Methuselah“, >4850 yo. Big Pine is also home to the Big Pine Paiute Tribe and sits in the widest part of the Owens Valley. From here, one can see the Palisade Glacier, the southernmost active glacier in the US. Historically founded as an agricultural (not mining) -focused settlement, today Big Pine is considered to have some of the darkest night skies in the US, making it a paradise for stargazing and astrophotography.

Next is Big Pine, a town we strongly associate with the turnoff to the Ancient Bristlecone Pine Forest. High in the White Mountains, this forest protects the oldest living trees on Earth, including “Methuselah,” which is over 4,850 years old. Big Pine is also home to the Big Pine Paiute Tribe and sits in the widest part of the Owens Valley. From here, one can see the Palisade Glacier, the southernmost active glacier in the US. Historically founded as an agricultural hub, today Big Pine is renowned for having some of the darkest night skies in the country, making it a paradise for stargazing.

Then comes Bishop. I didn’t know but this small town (in fact, the largest in the area) is “the Mule Capital of the World”, every Memorial Day weekend it helds “Mule Days” festival with mule parade, rodeos and country music concerts. The town was named after Samuel Addison Bishop, a rancher who together with partners realized that miners in nearby boomtowns needed a reliable food source and drove cattle into the valley to meet the demand—a true story of the American dream. Geologically, Bishop sits at the southern end of the Long Valley Caldera, a massive depression created by a supervolcano eruption 760,000 years ago. The magma chamber, still hot just a few miles beneath the surface, powers the region’s many geothermal features, including our favorites in the northern part of the caldera: the remarkable Hot Creek Geological Site and Wild Willy’s Hot Springs.

After passing through Mammoth Lakes, we traditionally stop at the Crestview Rest Area for its welcome shade and the charming family of tiny ground squirrels who live there. Halfway between this rest area and the June Lake Junction, a sign points to Obsidian Dome—a place we have yet to explore.

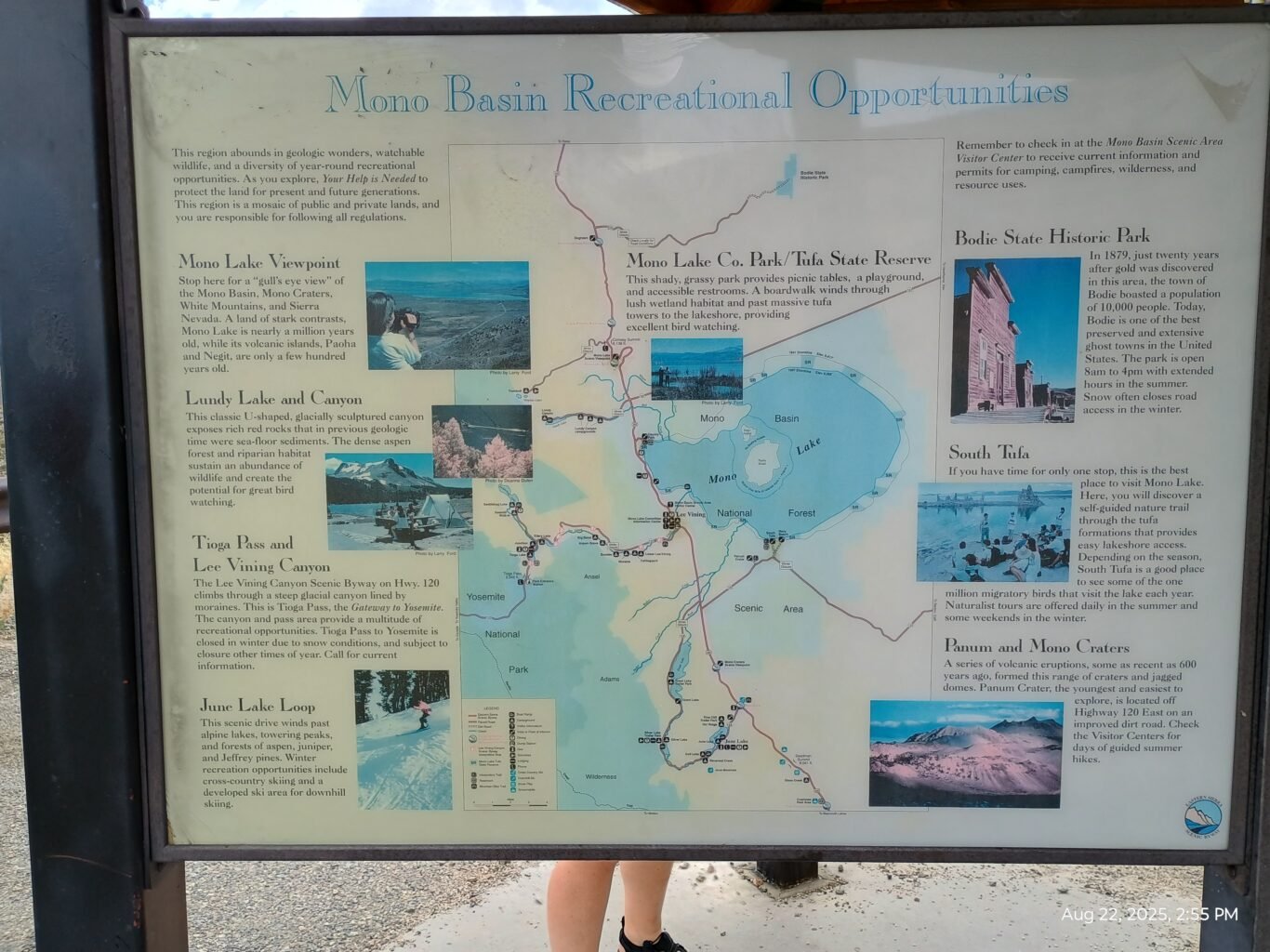

The road continues past the turnoff for Yosemite and leads to Mono Lake, another monument to ecological disaster, though this one was thankfully averted before the lake was lost completely. Monolake County park is our next traditional place to stop. We used to hike to the lake shore, but very recently because of big fire the trail was closed for rehabilitation, sadly.

From there, the route becomes a scenic drive through history, passing the site of Dog Town and the turnoff to Bodie, arguably the largest and best-preserved ghost town in whole USA. We travel through Bridgeport, the living county seat of the “ghost” Mono County, with its iconic 1880 courthouse. After Sonora Junction, the highway follows the West Walker River, hugs Topaz Lake, and briefly dips into Nevada where gambling in casinos is allowed but lotteries are not. Anyway, after refueling in rather nice Carson City (which appeared to be a state capital), a 20 minutes drive on US-50E and NV-342N leads up the grade to Virginia City. Silver and gold mined here fueled the boom of San Francisco in 1859-mid 1870s and defined the culture of the Old West. This is where a young Samuel Clemens first adopted his pen name, Mark Twain, while trying to capture the chaotic energy of the boom in his writing. Today, the entire historic district is honorably preserved, feeling less like a ghost town and more like a living museum, and it is absolutely worth a visit.

The drive from Virginia City down to Reno on NV-341, known as the Geiger Grade, could be easily considered as scenic. On the trip, we met a lonesome wild horse. She was old and appeared lame, possibly partially blind, as she emerged suddenly from the uphill scrub, passing very close to our car before disappearing down a small brushy path into the valley below.

At Reno, we turn to US-80 and then turned right to US-89 which guides us past Lake Almanor and directly to the Warner Valley Campground in Lassen Volcanic National Park.